Peacekeeping in Transition

How Bulgaria's post-communist chaos crept into Cambodia

When Nikola Nikolov and his fellow soldiers landed in Cambodia in 1993 after a 13-hour long flight, they were first hit by the unbearable heat. With their clothes soaked in a matter of minutes, none of them could tell if it was their own sweat or just the humidity. Still disoriented from the long flight, nothing could numb the childish enthusiasm, which had taken ahold of them. They were bearing witness to real palm trees when just recently they had to wait in a never-ending line for unripe bananas, a sign for the approaching new year in Bulgaria.

The roads, lined with potholes big enough to bathe in, were all mud and dirt. Along those roads, tiny wooden houses stood, ready to fall apart and be brought back up again by a people whose lives were always accompanied by war and death. Dressed in ragged and stained clothes, Cambodians swam and drank from the same bacteria-infused water, took care of their cattle, and gave birth to children they could not always feed.

The aromas that filled the stiff air battled for dominance as if they too, were in a war. Decaying wood presided over mahogany but then quickly gave way to spiced food. The soldiers, overwhelmed by the mysteries of this foreign country, never imagined their time in Cambodia will stay with them even after 30 years.

"I went there to test myself," says 57-year-old Nikolov.

Neatly lined-up cameras, acquired through the years and now obsolete, make the ordinary wardrobe in Nikolov's living room an eye-catching piece of furniture. Nikolov, a self-taught cameraman, spent close to a month's salary on his first camera in Cambodia in 1993. Otherwise a little shy and nervous to share his story, he readily pulls out a small mountain of photos as visual evidence of both the good and the bad moments in Cambodia.

At the beginning of 1993, he enlisted as a volunteer for the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) peacekeeping mission. Only 30 years old, Nikolov felt prepared to challenge himself and participate in the first peacekeeping mission Bulgaria ever took part in.

The U.N. peacekeeping operation began in 1992 and was organized following the 1991 Paris Peace Accords, which marked the official end of the Cambodian-Vietnamese war. By organizing the largest-ever mission of the time, the U.N. undertook a serious challenge never attempted before. The mission aimed to take a hold of an independent state's administration and organize and run democratic elections. UNTAC cost $1.6 billion with a total of approximately 22,000 military and civilian personnel deployed in Cambodia. The mission included 46 participating countries, one of them being the newly democratic Bulgaria.

"We were all a little bit crazy to go there," says Sergeant Ivan Ivanov.

Ivanov still feels the implications of his time spent in Cambodia. No matter rain or snow, Ivanov confidently walks around in leather male sandals without socks and is famous for it among his friend. Having spent the full 14 months of the mission driving a fuel tank in temperatures as high as 40 degrees Celcius, cold weather is bliss for him. A big and jolly man, Ivanov jokes loudly and interrupts his friends always followed by an apology, fully aware he will do it again in a few minutes.

Cambodia, a country located in Southeast Asia, had been ravaged by war for years. Once home to ancient Buddhist nations, the country became a French colonial territory in 1863. When it gained its independence back in 1953, Cambodians enjoyed peace for a short period.

Cold War machinations made their way to Cambodia in 1965 when the Vietnam War extended into the country. The U.S. involvement in the war resulted in the bombing of Cambodia from 1969 to 1973. Following a coup d'etat in 1970, the power fell in the hands of the Khmer Rouge led by Pol Pot, a Marxist-Leninist ruthless politician. The communist regime culminated in genocide, killing somewhere between one and three million people and destroying libraries, temples, and infrastructure. In 1978, Vietnam invaded the country and after 10 years, peace efforts finally began, resulting in the UNTAC mission.

Rural life, Cambodia, 1993. Personal archive.

Rural life, Cambodia, 1993. Personal archive.

When Bulgaria decided to participate in UNTAC, many Bulgarian men signed up, knowing very little about Cambodia, its climate, and the conditions. A total of 1,446 men, most of them in their 20s, became peacekeepers 9,000 kilometers away from home. Ten of them never returned. Six soldiers died in accidents while four were killed during Khmer Rouge attacks.

"We were all very different but there was something inside of us, which united us and cannot be seen at first glance," says Ivanov.

For Bulgaria, the mission was the country's first military experience since World War II. A socialist state since the coup d'etat in 1944, Bulgaria led a foreign policy of isolation. The totalitarian rule of Georgi Dimitrov and Todor Zhivkov, both prominent communist leaders, led to many repressions up until the fall of the regime in 1989. Bulgarians could not travel freely to Western countries, nor could they listen to Western news and radio. The Party propaganda flooded all aspects of people's lives.

After 1989, Bulgaria experienced a system of political pluralism for the first time in 45 years. The country began its difficult transition from a socialist country to a democratic republic, which is often cited to end with Bulgaria’s acceptance in the European Union in 2007. In 1990, Bulgaria held its first democratic elections, which were won by the rebranded Bulgarian Socialist Party. The unexpected outcome led to many protests and the widespread opinion that the elections were rigged. Meanwhile, the economic crisis intensified, stores were empty, and basic goods were in short supply. Mass protests throughout the whole country led to the government’s resignation.

At the end of 1991, the Union of Democratic Forces was the first right-wing party to win the elections. The new government's goals were a total shift of the old system by changing the economic and political conditions inherited by socialism. The economic reform began with laws about restitution and privatization. The reform, even though necessary, led to a sharp decline in the quality of life, inflation, and rising unemployment. The government's foreign policy also changed in the direction of warming up relations with the U.S.A. and Western Europe.

As a result of the new foreign policy, on April 15, 1992, the National Assembly made the decision to participate in UNTAC with 75 policemen and an infantry battalion of 850 peacekeepers. The length of the mission required one rotation of men in January 1993, meaning that some peacekeepers chose to return to Bulgaria while others took their places. The government hoped its participation would help establish the country’s international presence and reaffirm its desire to collaborate with Western countries.

With its decision, however, Bulgaria also took on a huge responsibility to recruit, train, and support soldiers, which would represent the country in an international mission of great importance. A responsibility for which Bulgaria was not entirely ready, considering the lack of military experience and its turbulent economy. Nevertheless, Bulgaria set on establishing peace in a distant war-torn country.

And then, the problems began.

On April 19, 1992, the Chief of Defense of the Bulgarian Army gave out an order, which stated that volunteers need to be recruited for 12 days. At the end of this period, the applications were reviewed and the approved candidates were selected in three days. In the U.N. requirements, it was said that only volunteers could be recruited. Further requirements for candidates were to be physically and mentally healthy, have good professional preparation, and not have previous criminal offenses.

The reality was that the time allocated for recruitment was not nearly enough. In the first part of the mission, most volunteers came from the military reserve and were undisciplined and not well-prepared. Close to a quarter had pending criminal charges and were running from the law, according to a Washington Post article from 1993. The rumors in media surrounding the mission and expectations for higher payment prompted many qualified volunteers to give up going to Cambodia.

“There were people who were running from justice, people who were not using their real names,” says Ivanov.

Before sending off the first group of volunteers, the Ministry of Defense conducted a survey to find out the reasons why men signed up. Based on the survey, the primary motivator was the money, which could help them buy an apartment or start a business once they come back. Secondary factors were the unemployment levels in the country and the opportunity to test themselves in a difficult situation. According to the survey, everyone hoped that after their return they would have a better life and more opportunities.

Nikolov, who went to Cambodia after the rotation in January 1993, still can’t understand up to this day why the Ministry of Defense let unqualified people without training and proper experience go on the mission.

“The recruitment process was a huge mistake. They should admit it but nobody has done it so far,” Nikolov believes.

The freshly recruited peacekeepers had less than a month for preparation before they were sent off to Cambodia in the first days of June. The overall preparation of the mission was rushed, which resulted in problems with the machines and food. According to Major Stefan Davidov, who was then Deputy Chief of Logistics, the time for training and preparation was not enough. Turning a group of strangers into a well-functioning and disciplined military division usually takes around a year.

The Soviet armored personnel carriers (APC) and trucks also turned out problematic in Cambodia. In Bulgaria, military commanders were getting rid of their oldest machines, sending them off to Cambodia. Machines, which had to protect the lives of men couldn’t even start; others lacked spare parts. Ivanov tells of a story when they were unloading the ship in Cambodia and one of the APCs wouldn’t start. They had to push the 15-ton machine to get it off the ship, while peacekeepers from other countries watched and wondered what is going on.

Nikolov, who was a mechanic and instructor for APCs, was puzzled when he got to his assigned camp and saw that the machine guns and combat equipment had been removed from the vehicle. His first job was to put the machine guns and the firearm in their place because there could be a danger at any moment.

“There were other very serious problems with the machine but in a week with the help of my colleagues, we managed to repair the machine and make it serviceable. Because not long after 15-20 days we had to react quickly to the rescue of our colleagues,” Nikolov says.

Davidov going through his notes from the mission, March 2021.

Davidov going through his notes from the mission, March 2021.

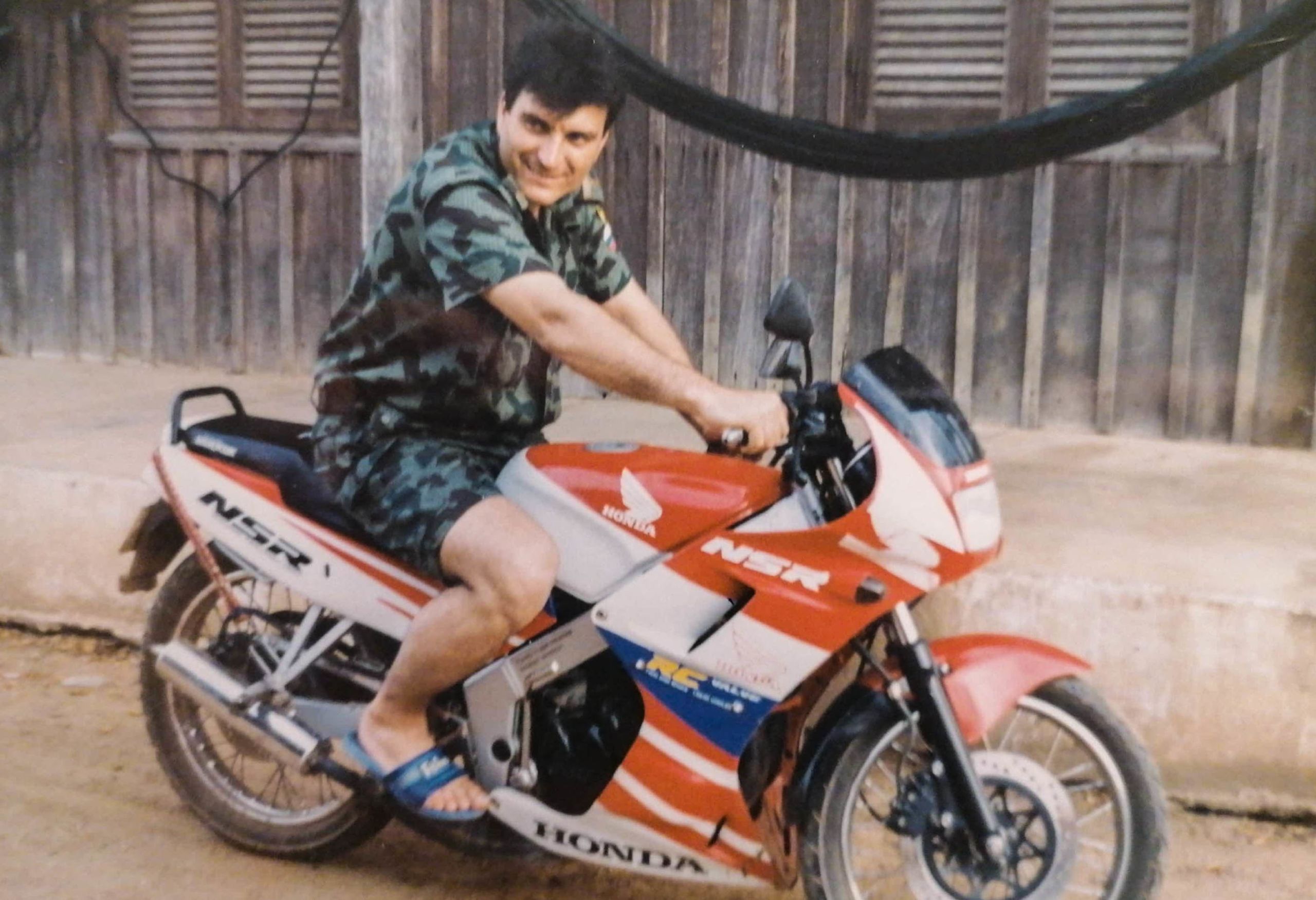

Davidov with a friend, Cambodia, 1993. Personal archive of Davidov.

Davidov with a friend, Cambodia, 1993. Personal archive of Davidov.

Private Ivo Hristoskov, one of the youngest participants in the mission who turned 19 there, recalls their training in Vratsa.

“An officer from third company came and he was supposed to prepare us. He told us such nonsense. He told us to bring garlic because in Cambodia there was none,” Hristoskov says.

As a young boy looking for adventures and a way out of looming adult responsibilities, Hristoskov signed up for the mission and became a translator and systems administrator. He is now one of the major actors in preserving the memories and documents from the mission by creating a digital archive.

As it turned out, Bulgaria, also responsible for bringing its own food supply to last for the first 60-day period, failed in this regard too. Davidov believes that the person responsible for the food failed to consider that the climate conditions in Cambodia will be different from the ones in Bulgaria. As a result, the canned food became a ticking bomb in the high temperatures. The veal had worms in it, and the halva, a traditional hard sugary treat, liquified.

During the first two months in Cambodia, the tension in the Bulgarian battalion was building up. Disciplinary violations began piling up. There was weak control on the side of commanders, which led to systematic problems with the discipline.

“I believe there are no guilty subordinates. The commander is always to blame for the preparation of his soldiers,” says Davidov.

The bad conditions and the lack of proper food and clothing suitable for the climate agitated soldiers. Severe discrepancies in living conditions, equipment, and pay created the impression in Bulgarian soldiers that they were not equal to other countries. Australians enjoyed generous pay and allowances, while Bulgarians ate canned food and awaited their first salaries.

On July 23, 1992, a protest in the battalion endangered Bulgaria's participation in the mission. A significant delay in the first salaries proved to be the tipping point for soldiers who demonstratively left their duties and headed to Phnom Penh where the Bulgarian embassy is situated. They addressed a written letter to the President of Bulgaria, demanding salaries according to the U.N. contract, better conditions, and regular correspondence. Two-thirds of the battalion, or about 600 men, signed the document and the salaries got to the soldiers in a day but the organizers of the protest were sent back to Bulgaria.

“When we got there, we were getting zero correspondence. We didn’t know what was going on in Bulgaria for months,” Ivanov remembers.

The average salary, which a U.N. soldier on the mission was supposed to get, was $800. Expenses were covered by each government and then reimbursed by the U.N. However, each soldier's pay was determined according to the respective law of the participating country. At the time, there was no such law written in the Bulgarian Constitution and this allowed the government to take some shortcuts and pay soldiers only half of the sum. When soldiers arrived in Cambodia, they realized they were severely underpaid compared to others. The protest led to a revision of salaries and full payment of the promised sum.

“Considering the bad conditions, the delay in salaries did not allow for people to go and buy food,” says Hristoskov.

Even with higher salaries and improving conditions, the overall discipline remained an unsolved problem throughout the mission. According to official records, by December 1992, 56 members of the battalion were sent home for disciplinary reasons. Bulgaria was a leader in another unfavorable ranking. The presence of so many UNTAC soldiers fueled widespread prostitution and close to 30% of Bulgarian soldiers contracted some form of sexual disease; less than a dozen came back with AIDS.

Bulgarians became infamous for smuggling snakes, monkeys, and other exotic animals upon their return, making the headlines of both international and Bulgarian media. Some soldiers drank while on duty, disregarded orders, and engaged in inappropriate behavior. Officers were not certain what to do because what they had studied in Bulgarian military schools was inapplicable in Cambodia.

“The problems didn’t get solved – they were just piling up,” Ivanov says.

As an experienced and educated military leader, Davidov went to Cambodia in 1993 with one goal in mind – to fix the mistakes that had been made.

A man of honor and enchanting charisma, his presence fills in the whole room. As if still in the military, the hierarchy in communication is kept in social settings. Whenever Davidov speaks, the rest of the men listen.

By going to Cambodia, he wanted to protect Bulgaria’s image and improve the discipline and morale among soldiers. His first task was to create written accountability of who goes where, what is used, and who carries the responsibility. At the beginning of 1993, some form of order found its way into the Bulgarian battalion.

“When he [Davidov] came, he brought in some peace and order among us,” says Ivanov.

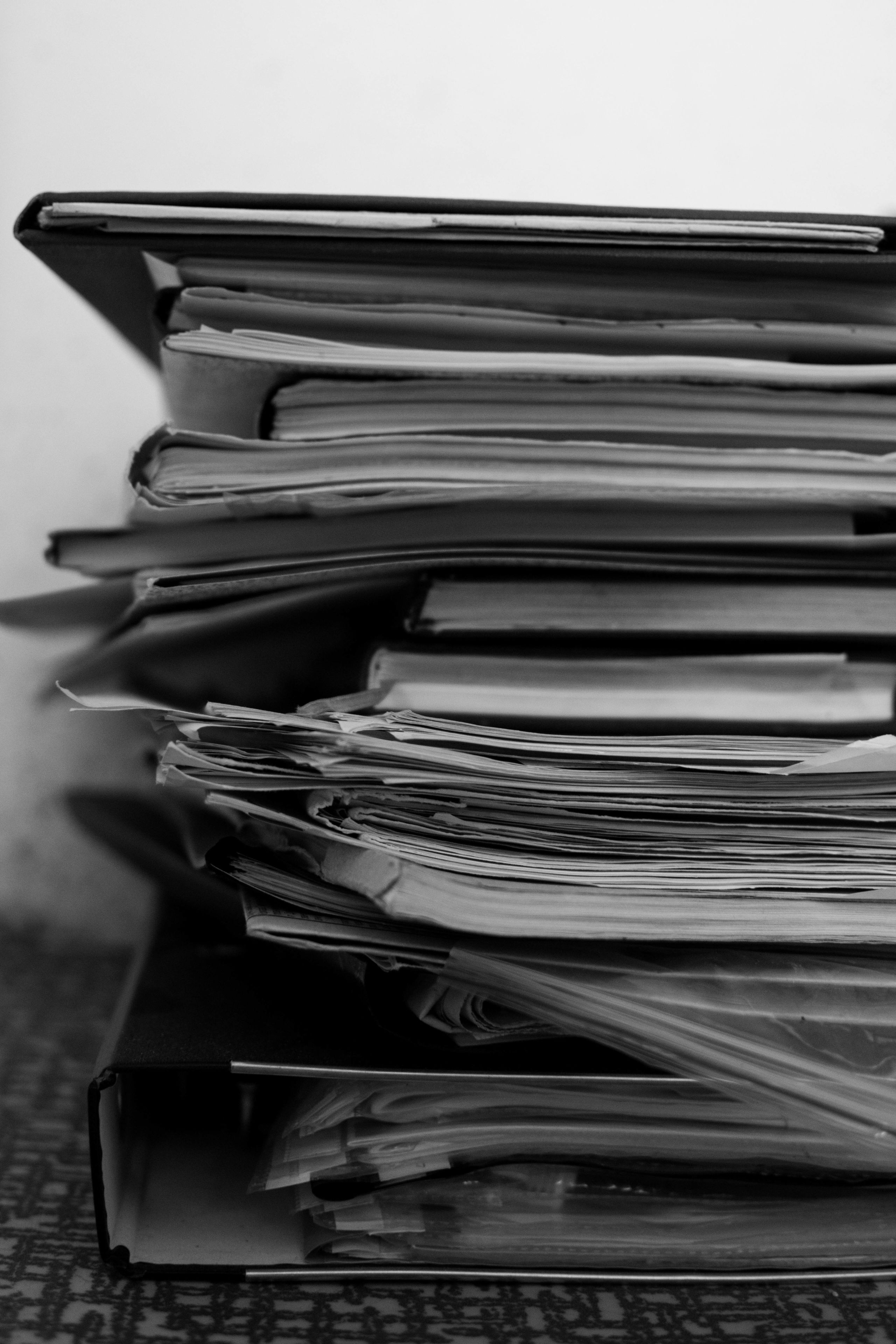

Davidov's pile of documents related to the mission, March 2021.

Davidov's pile of documents related to the mission, March 2021.

After Davidov landed in Cambodia, his first task was to meet his predecessor, who was not fully sober. On the next morning, he told Davidov he was happy to hand over his position because Davidov actually knew what needed to be done.

“The Bulgarian man doesn’t like to be told what to do. There were people with unnecessary confidence,” recalls Davidov.

Realizing the Bulgarian Army lacked experience in such conditions, Davidov wanted to analyze the workload of soldiers and the usage of machines in a tropical climate. By the time he arrived in Cambodia in January, three soldiers had died in accidents. As the election time was approaching, the Khmer Rouge was getting more agitated because it felt the U.N. was on the government’s side. On April 2, this tension culminated in the attack on Bulgarian soldiers in the Phum Prek district, where three soldiers were killed. Later in the month, dozens of Bulgarian soldiers suffered injuries, and one more was killed when the Khmer Rouge attacked the village of New Oral.

“The hardest part is bringing back your soldier in a coffin,” says Davidov.

While the events in April mobilized Bulgarian soldiers and made them more alert, the media and society in Bulgaria were in a frenzy. The public outcry was so huge that the families of soldiers organized a petition to demand the withdrawal of the battalion. Mothers went out to protest in an attempt to push government officials to act. The majority of soldiers, however, saw a possible withdrawal as shameful and did not wish to return in such a way. They wanted to finish the mission and protect the honor of their country.

Meanwhile, the emerging private Bulgarian media were reporting on the distant events based on government press releases and foreign media. Only Standart newspaper sent out actual correspondents to Cambodia. The governmental Bulgarian National Television also had a team in Cambodia, which produced a documentary film called “Silence in Cambodia.” The film mostly showed Bulgarians drinking rather than doing their actual duties.

Ivanov, Davidov, and Hristoskov claim that what was written in the media was mostly sensational and untrue. They believe that the media then contributed to the bad image of the mission and led to a lot of confusion and misinformation among Bulgarians.

“The information in the media was inaccurate,” says Davidov.

While the media, in general, did focus on sensational and out-of-context reporting, some media held higher standards and abided by the basic rules of journalism and ethical reporting. The media environment in the 90s, however, was largely shaped by the same people who were just recently writing socialist propaganda or were reporting to the State Security.

The history of Bulgarian private print media began right after the fall of the regime. The three daily newspapers with the biggest market share and circulation of the time were 24 hours, Standart, and Trud. Rumen Savov, who was sent to Cambodia as a correspondent in May 1993, was working for Standart at the time. He remembers that the editorial policy of Standart was to always include the two different points of view in a story.

“We were only getting information from the Ministry of Defense. It was necessary to hear what people in the battalion think,” says Savov.

First published in 1992, Standart’s main goals were to establish itself in the market and be a serious competitor to 24 hours, which came out a year earlier. With a lack of standards and ethical codes at the beginning of the 90s, the style of 24 hours and Trud was one of sensationalism, shocking titles, inverted word order, and lack of sources.

“We were trying to be different from the newspaper style imposed by 24 hours,” says Savov.

According to Savov, who has been practicing journalism since 1989, Standart relied heavily on facts and objectivity, avoiding unnecessary sensationalism. He agrees that the media played a role in creating a negative image of the mission but also notes the blame of the government that failed to organize the mission well.

“In Cambodia, things looked quite different [from all the rumors in Bulgaria]. There were problems in the overall organization. We were a little behind than the rest of the other countries,” says Savov.

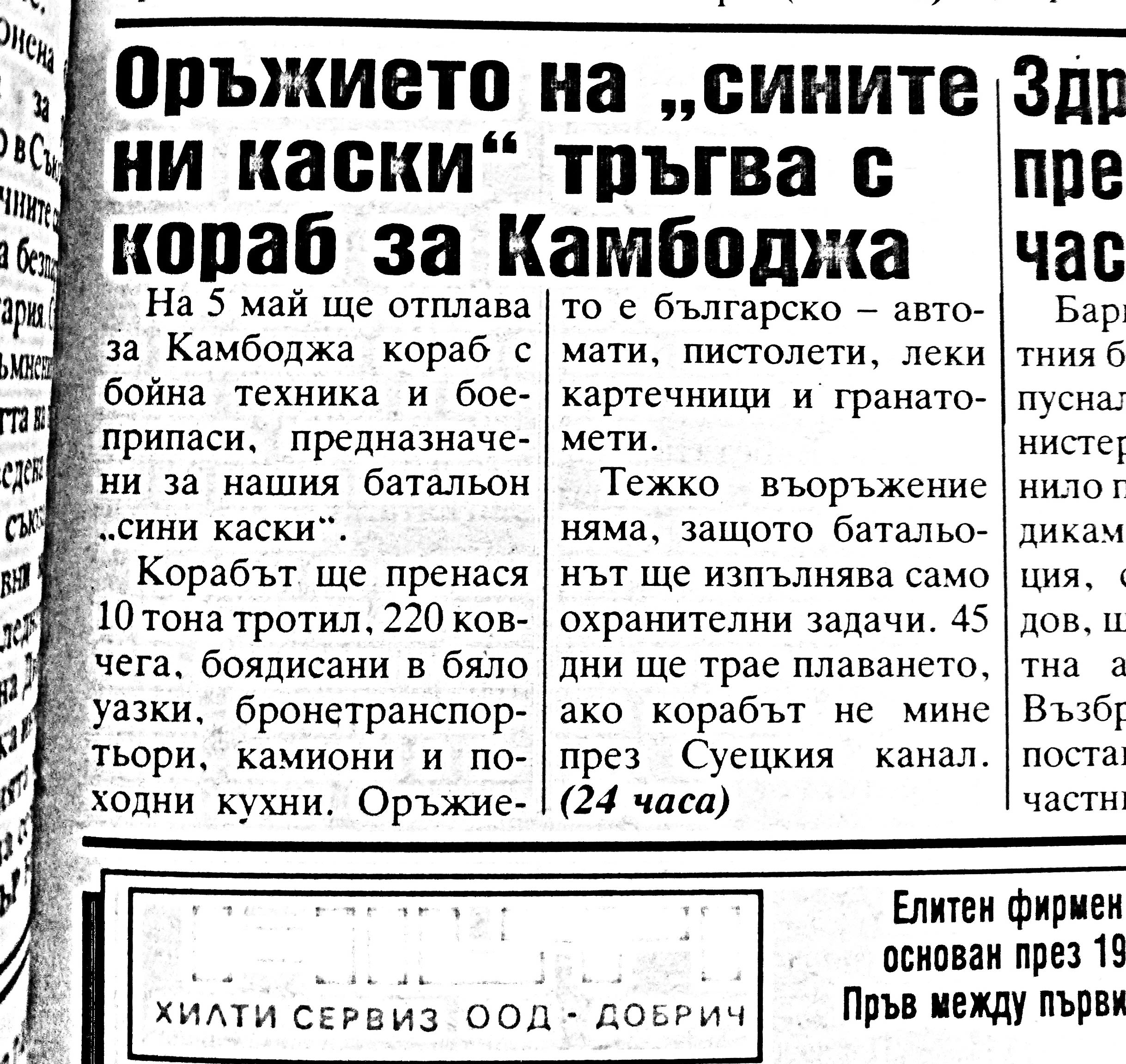

An article in 24 hours, which says that there are 220 coffins on the ship to Cambodia, 27.04.1992

An article in 24 hours, which says that there are 220 coffins on the ship to Cambodia, 27.04.1992

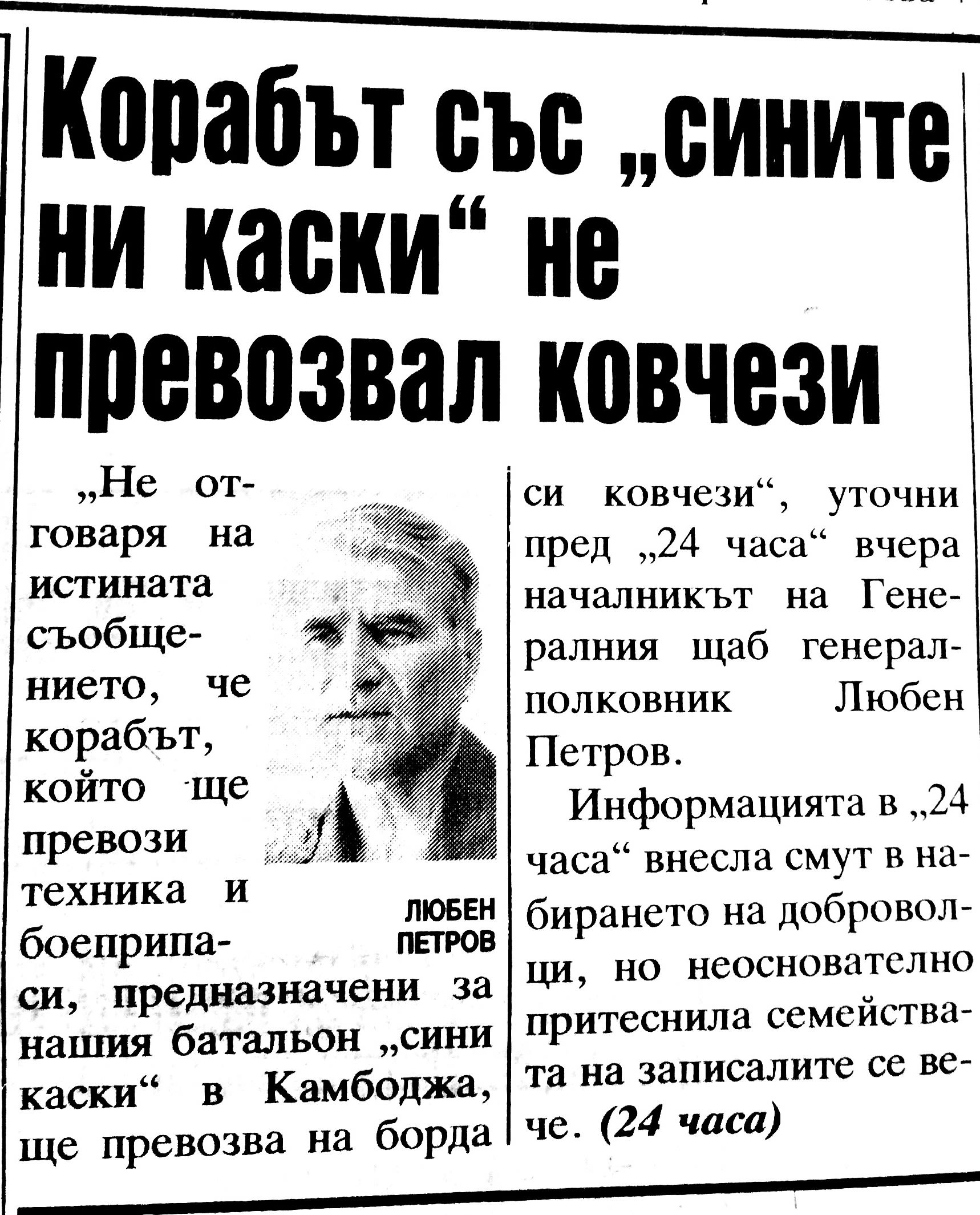

An article in 24 hours published one day later, which disproves that the ship carries coffins on board, 28.04.1992

An article in 24 hours published one day later, which disproves that the ship carries coffins on board, 28.04.1992

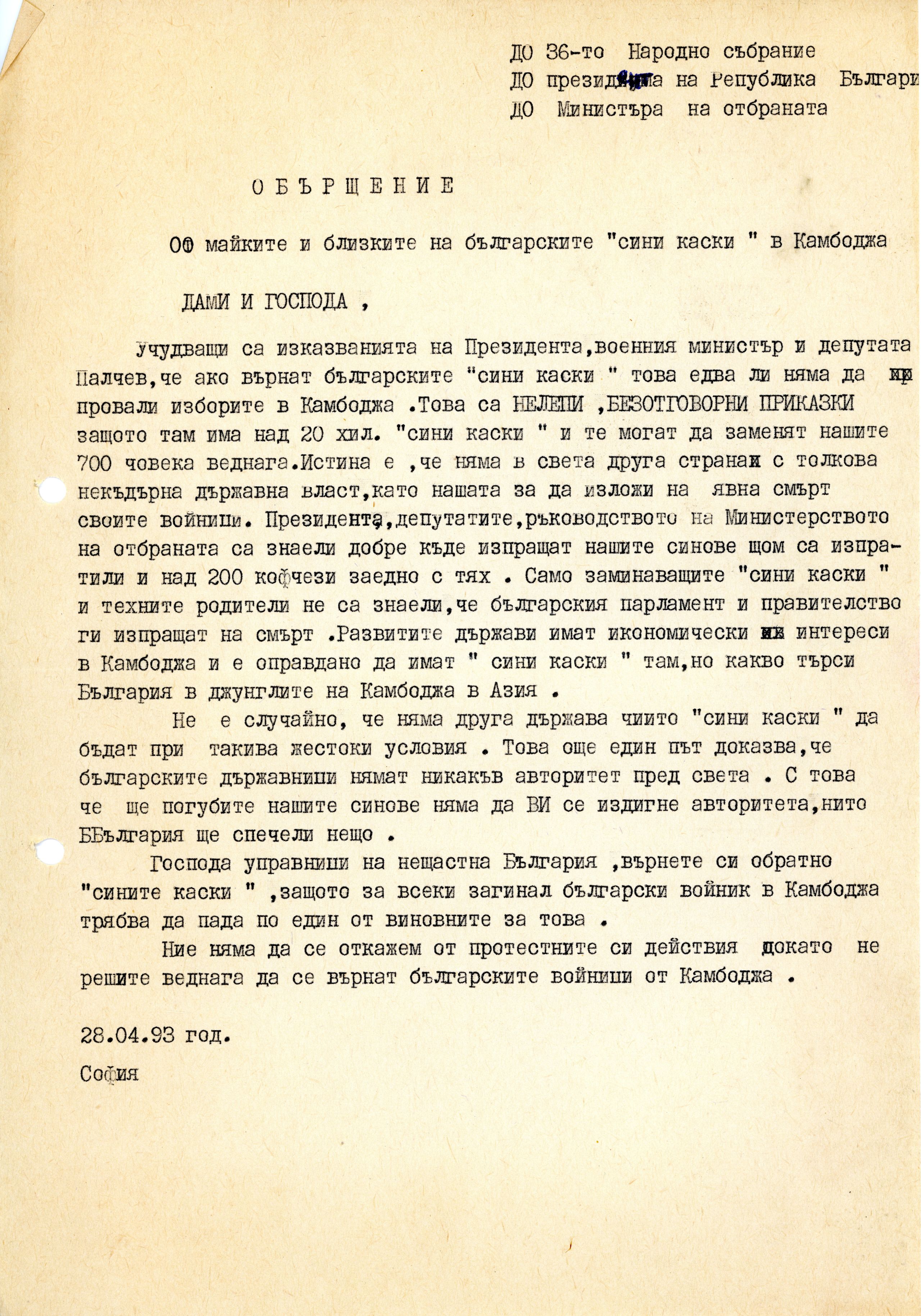

A letter from mothers and relatives addressed to the President and the Minister of Defense, asking why politicians knowingly send their sons to die along with 200 coffins, 28.04.1993

A letter from mothers and relatives addressed to the President and the Minister of Defense, asking why politicians knowingly send their sons to die along with 200 coffins, 28.04.1993

"We deserved something more."

When soldiers returned from Cambodia either after the rotation in January 1993 or at the end of the mission in August 1993, they faced the challenge of re-adaptation. Some peacekeepers had spent more than a year in the distant country, others were showing signs of PTSD, according to Hristoskov. There was no psychological help provided by the government to ease the process and assess their needs.

“When we came back, everyone started drinking. Some took a mortgage on their property and tried to start a business. A lot of people became drunks,” says Ivanov.

The problems after their return were intensified by the empty promises of the government. Promises of receiving higher military rank and medical insurance went unfulfilled. Despite the successful end of the mission and the spilled Bulgarian blood, the negative image of the "blue helmets", as dubbed by the media, still presided in society. Sensational media headlines, bad discipline, and the poor recruitment in the first part of the mission all built the stereotypical image of the Bulgarian "blue helmet" – a man who went to Cambodia to drink, have sex with prostitutes, and earn easy money while doing so. While it is undeniable there were some men who fit the image, for the most part, soldiers went to Cambodia and did their job but received no recognition upon return.

“Everyone was looking at us with envy, as if we were filthy rich. Or, as if we were lepers who had syphilis or AIDS,” says Davidov.

Davidov, who refused to blindly follow orders, faced repercussions back in Bulgaria. He was told to load four boxes but was not allowed to open them. Since he was responsible for the cargo on the ship, he firmly refused to go against his principles and let boxes with unknown content be loaded on his ship. As a personal vendetta for getting in the way of higher-ranking officials, Davidov was made accountable for every dollar spent on the mission. At the end, it was concluded he had stolen 700,000 leva.

“I had big problems in my career. Even though I was more than qualified, they never made me a general,” says Davidov.

Coming back from an international environment, Ivanov knew how soldiers in other countries are treated with respect in society, which was the total opposite of what they were experiencing in Bulgaria. He experienced problems within his family and has not spoken with his father for 10 years.

“Whatever motivation each of us had, it is a fact that we went out there and did something for the country. We deserved something more,” says Ivanov.

Almost 30 years after the mission, ex-peacekeepers are still fighting for something more. After several failed attempts throughout the years, in 2019, the Association of Bulgarian Veterans Peacekeepers became a reality. The organization aims to unite and connect peacekeepers from all missions and create a strong community. Hristoskov, Davidov, and Ivanov are all initiators of the association and active leading figures who provide full transparency and accountability for the organization's activities. They are trying to popularize the UNTAC mission, clear off the bad image, and help each other when needed. They rely on active members around the country and abroad to help create a network and reconnect with long-lost friends from the mission.

They self-organize and gather whenever they can and every member who wants to come is welcome, even those who cannot afford a meal at a restaurant. Hristoskov, who has been using social media since 2014 to reconnect with ex-peacekeepers, has created an extensive database with contact information and whereabouts of more than 600 men. According to him, more than 100 ex-peacekeepers have passed away throughout the years.

In the association’s Facebook group, which is the primary means of communication for members, photos and memories from the mission are shared almost every day. Long-lost friends announce they have met for the first time in 20 years. Fundraisers are organized for a member's sick relative. Tribute is paid on the days of the fatal attacks or accidents. They post. They comment. They remember.

And no matter how much the mission took away from their health, reputations, or personal lives, it gave them something more in return. It gave them the experience of a lifetime. Something worth remembering even today.